Immunotherapy Approaches for Lung Cancer

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality. Immunotherapy, particularly represented by immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), has emerged as a crucial treatment modality for lung cancer, achieving groundbreaking advancements in the management of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). ICIs targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) or the programmed cell death protein-1/ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) pathways have significantly improved patient survival rates, which are recommended as first-line treatment strategies for advanced NSCLC patients without driver alterations or with KRAS mutations. However, the response rates of these widely used ICIs are suboptimal, with only 10-30% of patients exhibiting long-lasting responses due to challenges such as tumor resistance, lack of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), and the presence of suppressive myeloid cells. Additionally, the development of acquired resistance and the occurrence of immune-related adverse events (IRAEs) pose substantial barriers to effective treatment. In recent years, novel ICIs have demonstrated promising results in preclinical and early clinical studies, reinforcing the pursuit of new therapeutic strategies aimed at overcoming resistance to traditional ICIs such as CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies.

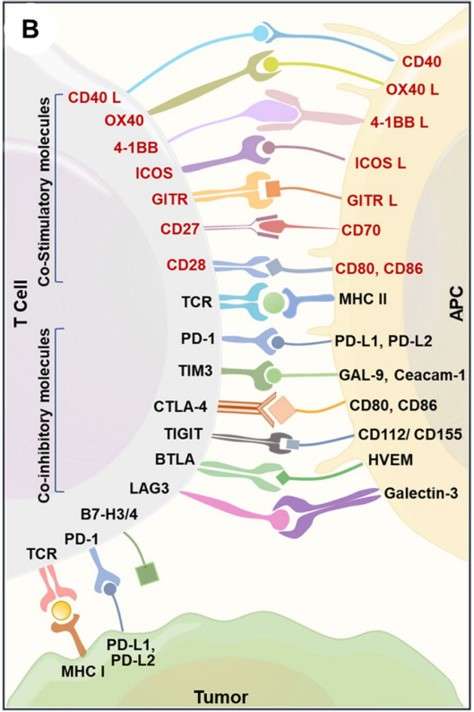

Fig 1. Immune interaction between T-cells, antigen-presenting cells, and cancer cells.1

Fig 1. Immune interaction between T-cells, antigen-presenting cells, and cancer cells.1

Novel Immune Checkpoint Targets

- T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT)

TIGIT has emerged as a significant immune checkpoint in recent years, mainly expressed by activated CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs), natural killer (NK) cells, and follicular helper T (Tfh) cells. TIGIT functions by binding to CD112 and CD155, which are expressed on antigen-presenting cells and tumor cells. Research indicates that dual blockade of PD-1 and TIGIT can enhance the functionality of CD8+ T cells and improve tumor rejection.

- T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3)

TIM-3 (HAVCR2) is a negative regulatory molecule primarily expressed on T helper 1 (Th1) cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (Tc1). Additionally, TIM-3 can be expressed by innate immune cells, including dendritic cells, NK cells, Tregs, and macrophages. In solid cancers, high levels of TIM-3 expression are associated with poor prognosis. Notably, the combined inhibition of TIM-3 and PD-1 demonstrates significant antitumor activity.

- Lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3)

LAG-3 is mainly found on the surface of activated CD4+/CD8+ T cells, B cells, NK cells, and dendritic cells (DCs). It plays a negative regulatory role in the cytokine secretion, activation, and proliferation of Th1 cells, allowing tumor cells to evade immune responses. Currently, 23 distinct blocking monoclonal antibodies and bispecific antibodies targeting LAG-3 have entered clinical research stages. Preliminary results indicate that LAG-3 exhibits a significant synergistic effect with PD-1 in promoting cancer immune evasion, positioning the combination of LAG-3 and PD-1 as a critical strategy in tumor immunotherapy.

- NK group 2 number A (NKG2A)

NKG2A is primarily expressed on the surface of NK cells and certain T cells, like CD8+ T cells and Th2 cells. HLA-E serves as the sole ligand for the heterodimeric receptor CD94-NKG2A, and its overexpression on cancer cells has been associated with poor clinical outcomes. Monalizumab (IPH2201), a monoclonal antibody targeting NKG2A, effectively blocks the interaction between NKG2A and HLA-E, demonstrating promising therapeutic effects in early clinical trials for lung cancer. Moreover, combinations of monalizumab with anti-EGFR agents, anti-PD-L1 agents, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and chemotherapy are being explored in clinical research for NSCLC.

- CD73

CD73, also known as ecto-5'-nucleotidase, serves as a metabolic immune checkpoint that is significantly upregulated in various tumors, including lung cancer. CD73 catalyzes the conversion of AMP to adenosine, which exhibits immunosuppressive properties, thereby obstructing anti-tumor immune surveillance in T cells, NK cells, dendritic cells, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). Preclinical research has clearly shown that CD73 is essential for encouraging tumor immune evasion. Targeting CD73, particularly with antibody-based therapies, can inhibit tumor progression and metastasis, showing synergistic effects when combined with PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies and/or A2A receptor inhibitors. In a Phase II clinical trial for NSCLC, the combination treatment involving the CD73 monoclonal antibody oleclumab (MEDI9447) exhibited significant improvements in progression-free survival (PFS).

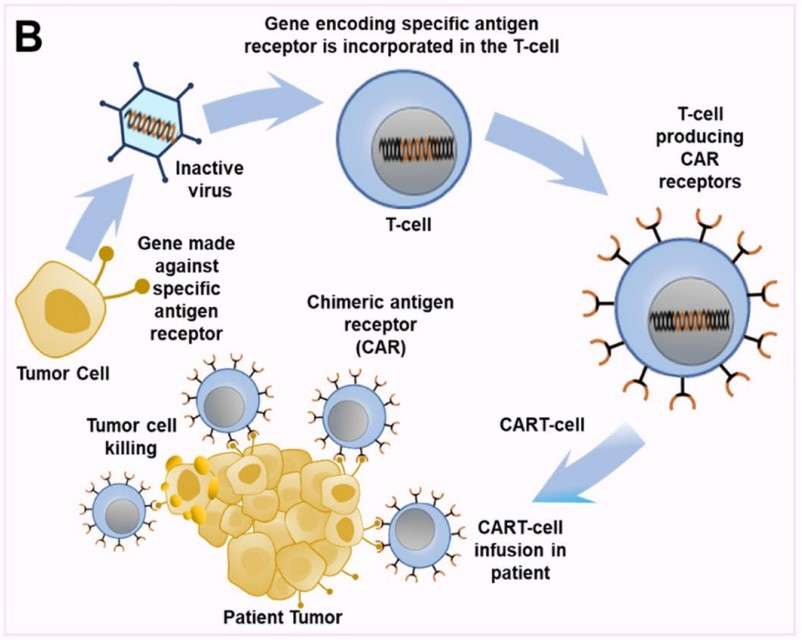

Cellular Therapy

In recent years, chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy has demonstrated significant efficacy in treating hematological malignancies. Recognizing the advantages of CAR-T cell therapy for blood cancers, numerous researchers have delved into its application for NSCLC, yielding promising preliminary results in preclinical research. Current cell-based engineered therapies for lung cancer are targeting several hopeful candidates, including mucin 1 (MUC1), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), mesothelin (MSLN), prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), glypican-3 (GPC3), protein tyrosine kinase 7 (PTK7), tissue factor (TF), erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular carcinoma A2 (EphA2), natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D), lung-specific X protein (LunX), receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 1 (ROR1), delta-like 3 (DLL3), and PD-L1.

It is crucial to emphasize that CAR-T cell therapy, when administered systemically, can provoke toxic reactions. Numerous clinical trials, extending beyond lung cancer, have demonstrated that patients undergoing this treatment have experienced severe and even fatal cytokine elevations. To mitigate these adverse effects, several strategies can be employed, including the use of antibody therapies to alleviate the impact of cytokine release syndrome, the incorporation of NK cells, or the development of CAR-T cells equipped with safety switches.

Fig 2. Mechanism of CAR-T therapy.1

Fig 2. Mechanism of CAR-T therapy.1

References

- Lahiri, Aritraa, et al. "Lung cancer immunotherapy: progress, pitfalls, and promises." Molecular cancer 22.1 (2023): 40. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0. The image was modified by extracting and using only Part B of the original image.

- Mamdani, Hirva, et al. "Immunotherapy in lung cancer: current landscape and future directions." Frontiers in immunology 13 (2022): 823618. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0.